BAHEA NAMOOR

Film Director

DEPORTEES

Israel has displaced Palestinians in many ways, including through deportation. Exiling them from Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), this is a policy prohibited under international law.

Since the establishment of Israel in 1948, deportation has been used to expel Palestinians from their land, both individually and en masse. The Fourth Geneva Convention, adopted in 1949, prohibits mass deportation from occupied territories.

Deportation or forced displacement of people from occupied territories is also seen as a war crime under the Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court.

Israeli military commanders can deport Palestinians under the Defense (Emergency) Regulations, 1945, which remain effective in the OPT.

On a cold December day in 1992, 415 Palestinians from the OPT were expelled to South Lebanon, after deportation orders were issued in the West Bank and Gaza Strip without any prior notice to the families. Deportees were handcuffed and blindfolded, and put in buses to be driven to South Lebanon. The convoy stopped en route for a few hours, while the Israeli High Court debated the legality of the deportations – only to then rule in support of the government’s position. As the buses rolled and made way to the north of Palestine, Lebanese authorities stopped them from entering its territory. Nawaf Al Takuri was inside one of the buses when it was pulled over five kilometers north off the Israeli border and it was decided that the inmates will walk back to Palestine.

A long line of men in crumpled, green, trench coats, shivering in the cold, slowly made their way to the border – only to be met with a wall of bullets piercing the cold, winter air. Israeli soldiers refused to let them in. More than 400 men were now stuck in no man’s land at Marj Al Zuhur, a valley between Israel’s ‘security zone’ and Lebanese-controlled territory, where they were forced to stay for a year in rickety, makeshift tents. Poems were written, and read aloud in gatherings around the fire for solace and comfort – but soon the verses became a call for change.

“We formed a leadership committee. We built a store and prayer room using tents. We even had our own university.” Nawaf Al Takuri said.

For most of them, the forced exile in no-man’s land became an opportunity to come together and create a protest movement that could attract media attention and force Israel to concede its mistake. The mass deportation, or what many called collective punishment, by Israel was now beginning to backfire as it became an international story.

“Was it an embarrassing situation? Of course. They protested in Marj Al Zuhur in front of the cameras”, Yigal Palmor from the Israeli Foreign Ministry said.

The United Nation Security Council condemned Israel’s actions, stating that they were contrary to the Fourth Geneva Convention and calling for an immediate return of all the deportees.

Israel was forced to bring them back. Most returned to their families, while 17 were deported with no prospect of return – including Nawaf Al Takuri, who was sent to Syria. Israel banned his father from visiting him for ten years, and his mother only saw him four times in 20 years.

“It was forced deportation for the entire family. We’re separated from each other. I left my son when he was five months old and saw him next when he was two years old. He thought I was his uncle, not his father”, Nawaf Al Takuri said.

Almost a decade later, during the Second Palestinian Intifada, there was another mass deportation. In 2002, Israel struck a deal for a few Palestinian fighters who, for 38 days, had taken refuge inside Bethlehem’s Church of Nativity in the occupied West Bank. Under a U.S.-brokered agreement, the Palestinians were granted safe passage from the Israeli-besieged church, on the basis that 39 of them were deported to Europe and the Gaza Strip.

Again, in 2011, another 180 Palestinian prisoners were freed and deported as part of an agreement with Hamas to free captured Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit. The deportation meant hope for those who yearned to escape the thick prison walls separating them from their families and loved ones, but the reunion came at a cost.

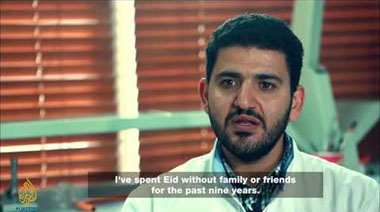

“‘On the bus, a detainee said; I've been in prison for 20 years, but I've never felt far from home." He said: "Now I know what it means to be an exiled.”’ Tayseer Sabih who was deported to Turkey talking.

For now the deportees try to make a life in foreign countries and continue their struggle for Palestine from a distance of miles but not of the heart.

WATCH THE FILM

ADMINISTRATIVE DETENTION

BORDERS

INTIFADA

COLLECTIVE PUNISHMENT

OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN

TERRITORIES

PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY

CREDITS

DIRECTED BY

BAHEA NAMOOR

ASSISTENT DIRECTOR

MOHAMMED ALHAJ YASEEN

SABA SHARQAWI

CAMERAMEN

YORAI LIEBERMAN

HANNA ABU SAADA

EDITOR

WALID ALALARI

MUSIC BY

NAJATI AL-SULOH

PRODUCTION HOUSE

VISION, JORDAN

COMMISSIONING SENIOR PRODUCER

RAWAN DAMEN

PRODUCTION YEAR

2014

REVERSIONED BY AL JAZEERA WORLD TO ENGLISH – 2015

COPYRIGHT © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FOR AL JAZEERA

RETURN TO TOP